Considering Totalitarianism

- Posted by arendt

- Posted in banality of evil, character, displaced persons, education, ethics, evil, Hannah Arendt, personal responsibility, Politics, public life, public space, teachers, The Origins of Totalitarianism, thinking

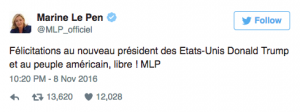

The response around the globe to the election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States has ranged across a spectrum. Applause came, of course, from Trump supporters who voted for him. The majority of these were white voters, men and women, and not only from the beleaguered rust belt states suffering from job losses in the manufacturing sector. Cheers rose among neo-Nazis in the U.S. and abroad, right wing rulers, such as Vladimir Putin of Russia, Reycep Erdogan of Turkey, and potential right wing rulers such as Marine Le Pen of France, Geert Wilders of The Netherlands, and Nigel Farage of the UK. Yet, even more moderate global leaders sent their congratulations and offers of support.

The response around the globe to the election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States has ranged across a spectrum. Applause came, of course, from Trump supporters who voted for him. The majority of these were white voters, men and women, and not only from the beleaguered rust belt states suffering from job losses in the manufacturing sector. Cheers rose among neo-Nazis in the U.S. and abroad, right wing rulers, such as Vladimir Putin of Russia, Reycep Erdogan of Turkey, and potential right wing rulers such as Marine Le Pen of France, Geert Wilders of The Netherlands, and Nigel Farage of the UK. Yet, even more moderate global leaders sent their congratulations and offers of support.

At the other end of the spectrum, among those who had fought against Trumps’ victory, a deep sense of mourning set it. Then fear and anger began to grow. Perhaps the U.S. was not really headed into uncharted territory. On the contrary, many commentators pointed to alarming indicators that the U.S. might be witnessing the crystallization of a new form of totalitarianism. In fact, the ease with which so many who had opposed Trump so strongly–calling him a dangerous and narcissistic demagogue, unfit to assume the mantle of the most powerful leadership position in the world–now seemed eager to cast his election in “normal” terms (“The people have cast their vote; let us move along with a smooth transition,” were words not infrequently heard) was perhaps the most alarming sign of all.

In a compelling essay in the New York Times, Teju Cole wrote about this process of normalization:

In the early hours of Nov. 9, 2016, the winner of the presidential election was declared. As the day unfolded, the extent to which a moral rhinoceritis had taken hold was apparent. People magazine had a giddy piece about the president-elect’s daughter and her family, a sequence of photos that they headlined “way too cute.” In The New York Times, one opinion piece suggested that the belligerent bigot’s supporters ought not be shamed. Another asked whether this president-elect could be a good president and found cause for optimism. Cable news anchors were able to express their surprise at the outcome of the election, but not in any way vocalize their fury. All around were the unmistakable signs of normalization in progress. So many were falling into line without being pushed. It was happening at tremendous speed, like a contagion.

Evil settles into everyday life when people are unable or unwilling to recognize it. It makes its home among us when we are keen to minimize it or describe it as something else. This is not a process that began a week or month or year ago. It did not begin with drone assassinations, or with the war on Iraq. Evil has always been here. But now it has taken on a totalitarian tone.

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt wrote about the appeal of mass movements to the displaced, those who, for whatever reasons of race or class or gender, feel as if “their” world has been sundered:

movements conjure up a lying world of consistency which is more adequate to the needs of the human mind than reality itself; in which, through sheer imagination, uprooted masses can feel at home and are spared the never-ending shocks which real life and real experiences deal to human beings and their expectations.

It may be, as Roger Berkowitz has argued in a recent post, that Trump’s “movement,” a term which Trump used frequently to describe his supporters, cannot (yet) be called totalitarian. Berkowitz wrote:

there is no coherent ideology underlying Trump’s movement. The very premise of totalitarianism is that there is a single, unifying, total idea — an ideology — that is to be actualized and affirmed. Trump has no such governing idea. His pragmatic openness characterizes his particular movement and is what makes his movement both so popular and so dangerous. It is a 21st-century movement in the sense that Trump, as its leader, does not insist on any kind of fidelity to a single idea.

Yet, as Arendt warned in Origins, the form totalitarianism took in the 20th century would not be the same as what it might become in the future, in our century. The very amorphousness of Trump’s “ideology” is, as Berkowitz notes, its ability to empower “a uniquely American and individualist version of a movement, one that grants individuals and groups license to create and defend their own meaningful realities.” Could this shape-shifting, ever-present targeting of myriad “others” to explain the source of one’s personal failures, coupled with the normalization of Trump as a fairly and democratically elected leader, signal the possibility of the most frightening and all-encompassing form of totalitarianism yet?

The masses who supported and continue to support Trump’s “vision” may have a common enemy in the Washington elites, whom they blame for failing them. But without the racist and sexist bigotry Trump vocalized, whose fallout we are already witnessing, the so-called “forgotten men and women” would have had only those the 1 % to blame. Now they have those elites and many vulnerable others as well to scapegoat and villify.

This is a teachable moment. I invite those of you who know educators to apply for teh 2017 NEH Seminar on the political theory of Hannah Arendt. Together we will examine the dynamics of totalitarianism and questions of responsibility and judgment in the face of its possible recurrence.